In early 2014 I’ve started research on the life and work of the Bauhaus Architect Arthur Korn. Korn has long been overdue a full length critical study of his life and work and the circumstances that surrounded him. In spite of the enduring popular interest in the spirit and ethos of Bauhaus, his work, and especially his early fascination with socialist architecture, has been all but forgotten. This research has been envisioned as a collaborative project with Sandra Križić-Roban, the senior research associate at the Institute of Art History in Zagreb. Sandra and I spent weeks in the archives of Berlin, Zagreb, Belgrade and London in an attempt to unravel the details of his life. The draft below is my initial contribution to this ongoing project. © All writing, unless otherwise credited, is by Alexandra Lazar.

ARTHUR KORN: AN ANALYTICAL AND UTOPIAN ARCHITECT

Architecture is Symbol. Radiation. Tendency of order — of music, of an impetus to the end. Embracing and dissolution. The building is no longer a block, but a dissolution into cells, a crystallization from point to point. It is a structure of bridges, joints, shells, and pipes. Shells, enveloping and discharging air between themselves like fruit. Pipe supports. Within it air flows making it firm and curved.

Thus begins “Analytical and Utopian Architecture” by the Bauhaus architect Arthur Korn (1891-1978). By 1923, when 32-year-old Korn published his first text and a manifesto of architecture, he has already worked on town planning, collaborated with Erich Mendelsohn and built houses and interiors in partnership with Sigfrid Weitzmann. Over the next decade he has built numerous factories, shops, offices, department stores, and co-created a Plan for Berlin in association with the Collective for Socialist Building (1925-’34).

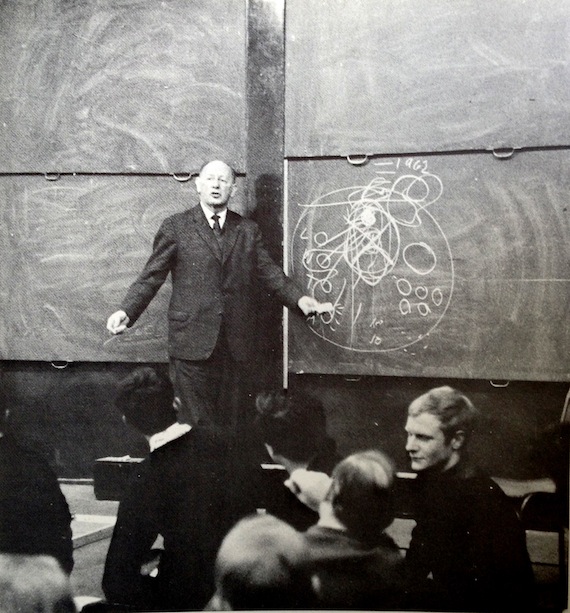

Although Korn will be among those fortunate enough to escape the nazism, the continuation of his career in England 1937-67 also signaled the end of his practice as an architect. While he is remembered for his unfailing teaching practice at the Oxford School of Architecture and the AA School of Architecture in London where he continued to work till his retirement in 1967, the very last project that he has built were the eight flats on Lettsom Street, Camberwell, in association with F. R. S. Yorke over thirty years prior, in 1938. In England, his strive towards modern architecture has failed to take a material form.

Why? Korn was clearly a gifted architect and town planner and a much-liked pedagogue. Yet the combined stigma of continental modernist architecture – not much appreciated in England at the time – and, perhaps more importantly, his strong socialist ethos, have likely contributed to the fact that Korn did not leave his mark on postwar architecture in England in the same way as some of his other expatriate colleagues did. Arthur Korn remains unfamiliar to most contemporary historians of architecture, not to mention the educated public.

Current research in England, which Korn has made his home from 1937 till his retirement, shows that Korn was unable to maintain his practice as an architect and planner, choosing (or being persuaded to choose) a career as a pedagogue instead. Korn’s ideological background – he was a committed socialist and a Marxist – was not welcome in England. It prolonged his internment in the Hutchinson camp, severed some professional connections and friendships, and arguably affected his overall professional involvement, both as town planner and practicing architect, and as theorist and member of MARS, CIAM, RIBA and other professional organisations, of which he became the increasingly withdrawn member.

Arthur Korn was a German Jewish architect and urban planner. Born in Breslau, Lower Silesia, Korn studied at the Luisenstadtisches Gymnasium (Real-Gymnasium) in Berlin, a carpentry trades school (c.1908-1909), and attended the Royal College of Arts and Crafts in Berlin (1909-1911). From 1911 he started to work as an architectural assistant in Halle and Berlin. During 1914 while briefly working in the town planning office of greater Berlin, he came under the influence of Raymond Unwin’s recently translated Town Planning in Practice (1909).[1] Sir Raymond Unwin (1863-1940) was a prominent and influential English engineer, architect and town planner, with an emphasis on improvements in working class housing. Unwin was a technical adviser to the Greater London Regional Planning Committee in 1929, and it is likely that his two reports (published in 1929 and 1933) influenced Korn’s subsequent Plan for Berlin (1934).[i]

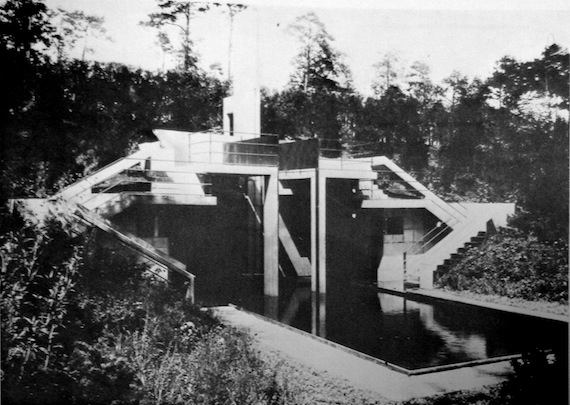

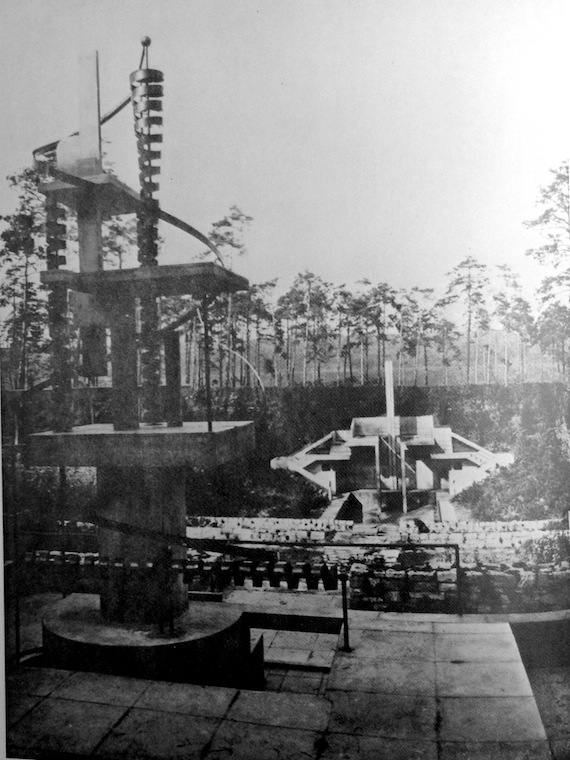

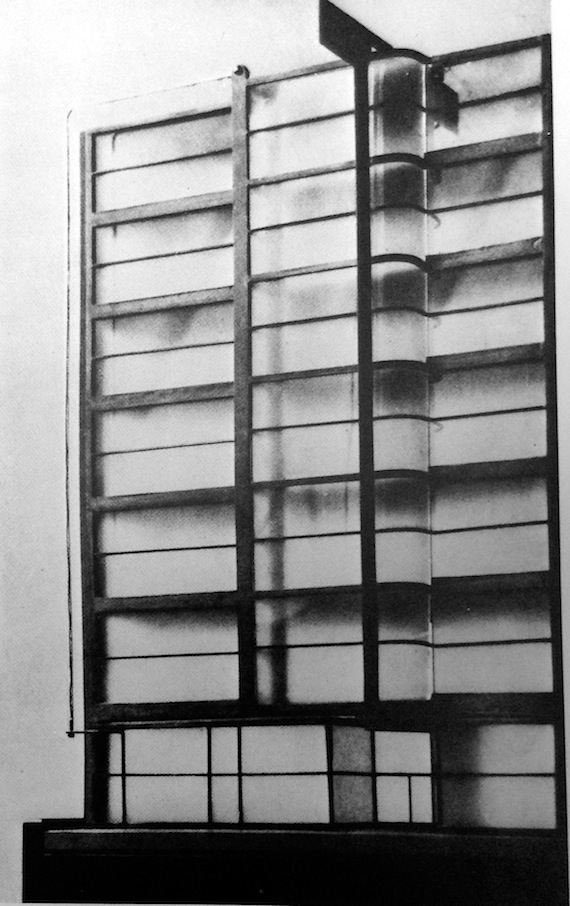

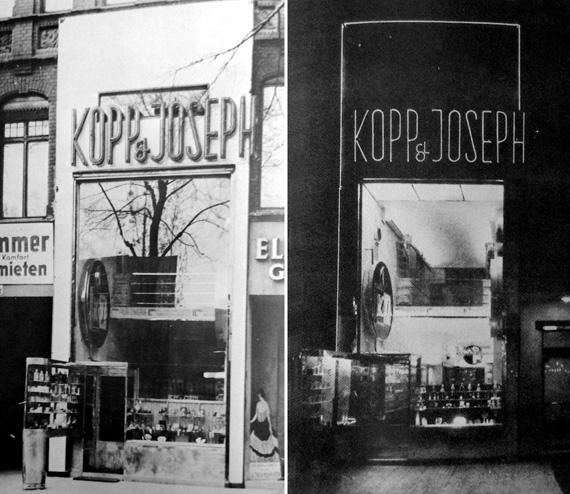

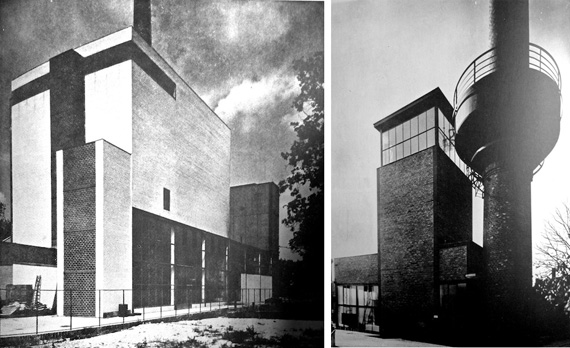

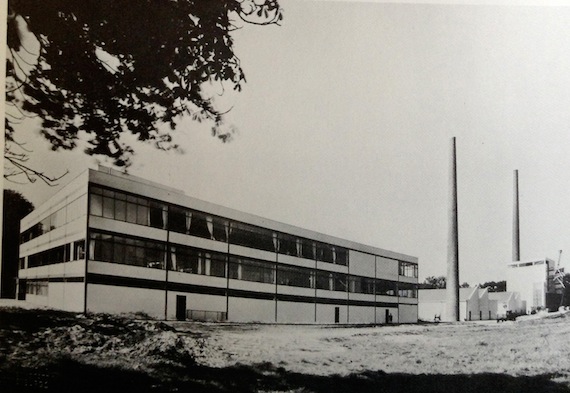

Following his war service (he was awarded the Iron Cross), Korn briefly worked with Eric Mendelsohn in Berlin, mostly on Mendelsohn’s Exhibition and a settlement of forty-six houses (1919).[2] From 1919 to 1922 he worked on his own, before forming a partnership with Dipl.-ing. Sigfried Weitzmann,[3] in Uhlandstrasse 175 in Berlin. The partnership was fruitful. Over the next ten years they built eight factories, seven shops (notably three shops for Kopp and Joseph, Kurfürstendamm, Tauentzienstrasse and Potsdamerstrasse, Berlin), and numerous offices, houses and interiors together.[4] Photographs of Korn and Weitzmann’s Villa Goldstein in Berlin were published in Walter Gropius’s seminal visual anthology of the new architecture, Internationale Architektur (1924); Korn’s business centre for Haifa, Jerusalem won second prize in the competition and was included by Gropius in Volume One of the Bauhaus books (Internationale Architektur, Munich 1925).[5] Finally in 1929, Korn publised Glas in Bau und als Gebrauchsgegenstand, a lavishly illustrated book that highlighted the potential of the new architecture and materials.

During the 1920s Korn was actively associated with various architectural groups, such as Novembergruppe (he was its secretary from 1924)[6] and Der Ring Berlin (1926-33), until both groups were forced to dissolve.

However, Korn’s true interest was in socialist town planning. This was further stimulated by a trip to the USSR in 1929 (he went as a consultant for a prototype hotel for Inturist), during which he made contacts with Soviet modernist architects and planners. The same year Korn co-founded the Collective for Socialist Building in Berlin and made proposals for the future development of Berlin, which were exhibited in 1930.

Korn’s fascination with socialist planning was in no way unusual. This was a period when many modernist architects freely turned towards the Soviet Union for inspiration and its ambitious large-scale projects, following the disillusionment with capitalism and the Great Crisis of the 1929. (This was the time when Le Corbusier creates his proposal for the Tsentrosoiuz building and the Palace of the Soviets.) The historian Ross Wolfe writes eloquently about this:

‘The Soviet Union alone had presented the modernists with the conditions necessary to realize their original vision. Only it possessed the centralized state-planning organs that could implement building on such a vast scale. Only it promised to overcome the clash of personal interests entailed by the “sacred cow” of private property. And only it had the sheer expanse of land necessary to approximate the spatial infinity required by the modernists’ international imagination. The defeat of architectural modernism in Russia left the country a virtual graveyard of the utopian visions of unbuilt worlds that had once been built upon it. It is only after one grasps the magnitude of the avant-garde’s sense of loss in this theater of world history that all the subsequent developments of modernist architecture in the twentieth century become intelligible. For here it becomes clear how an architect like Mies van der Rohe, who early in his career designed the Monument to the communist heroes Karl Liebneckt and Rosa Luxemburg in 1926, would later be the man responsible for one of the swankiest monuments to high-Fordist capitalism, the Seagram’s Building of 1958. And here one can see how Le Corbusier, embittered by the Soviet experience, would go on to co-design the United Nations Building in New York, after briefly flirting with Vichy fascism during the war’.[7]

Yet whereas most perceived it as an opportune episode (and later, like Corbu, turned to the Americas), the socialist idea resonated deeper with Korn, who maintained his socialist ethos, in one way or another, for the rest of his life.

Arthur Korn visited England in 1930 and again in 1934 with Walter Gropius, as a member of the German delegation to CIAM. This was a year after the legendary CIAM Conference of 1933 in Athens, ‘The Functional City’, when its members drafted the Athens Charter, an urban planning charter that would be used as a springboard for all future urban development. The Athens Charter, drafted and reviewed by Le Corbusier, Van Eesteren, Josep Lluís Sert, Karl Moser, Rud Steiger, Roman Piotrowski, Piero Bottoni, Héléna Syrkus and Wells-Coates, contained ninety-five resolutions based on the analysis of thirty-three cities and a synthesis of studies about the individual and the collective. In many ways the CIAM manifesto, the Athens Charter intended to advance the cause of ‘architecture as a social art’, and as such will become the single most influential document that formalized the principles of the Modern Movement and affect urban planning after WW2. ‘Life flourishes only to the extent of accord between the two contradictory principles that govern the human personality; the individual and the collective’ (Resolution 2).

However, the ideological rift was already there. The strongly Marxist Polish group (headed by Héléna Syrkus) were critical of the lack of attention given to the social and political issues, which was reflected in Resolution 91: ‘The course of events will be profoundly influenced by political, social and economic factors’. This was counterbalanced with Le Corbusier’s quest for individualism: ‘The dimensions of all elements within the urban system can only be governed by human scale’ (Resolution 76).[8]

In 1934, the effects of the freshly drafted Athens Charter were resonating strongly among the modernists. Korn and Gropius both joined the British arm of CIAM, MARS; but while Gropius stayed in England and commenced his fruitful working partnership with the renowned architect Maxwell Fry, Korn returned to Germany, fully aware of the implications of this return. After Hitler’s accession to power and the incorporation of the Bund Deutscher Architekten (BDA) in the Reichskulturkammer, Korn was forbidden to practice architecture in Germany.[9]

Korn’s contemporary and colleague, Edward Carter, says of this period:

‘Gropius stayed on in partnership with Maxwell Fry but Arthur Korn, for whom the Nazi regime had deeply sinister implications both politically and racially, returned to the continent for another three years. The CIAM meeting threw him at once into the intellectually exciting group of MARS at a time when the enlightenment and experience of continental architects were warmly welcomed as consolidation of the still groping and underemployed MARS members. Etchells’ Crawfords’ building had been up for four years, unique as a demonstration of things to come; Fry was building Sassoon House and Sun House was starting; Mendelson and Chermayeff were building the Bexhill Pavilion; Tecton had been going for several years, the Gorilla House and the Penguin Pool had been built and Highpoint I was building; Wells Coates was building Lawn Road flats; and Gibberd, with whom Korn stayed during his 1934 visit, was building Pullman court. There were still four years to go before the Burlington Galleries exhibition was to put the total argument of modern architecture before the uninterested British public. At this time the modern architectural achievement in Britain was exemplified by some twenty scattered buildings, but MARS was at a high point of its energies as a research and propagandist body and ready for the contributions that Gropius, Breuer, Mendelson and soon Arthur Korn could make. Although CIAM had concerned itself from the start with the widest social and urban planning implications of modern architecture we had to wait until Arthur Korn returned in 1937 for his influence to translate CIAM/MARS ideas into the actuality of Greater London Planning’.[10]

Instead of staying on in England in 1933, Korn emigrated to Yugoslavia, where he worked as an independent architect and planner in Zagreb between 1935-37. According to the brief note in his 1967 biographical summary, Korn worked on three interior decoration schemes, a Town Plan Competition with Vladimir Antolić and projects for three textile factories in Zagreb.[11] This period remains largely unmentioned in his future biographical summaries in England.[12]

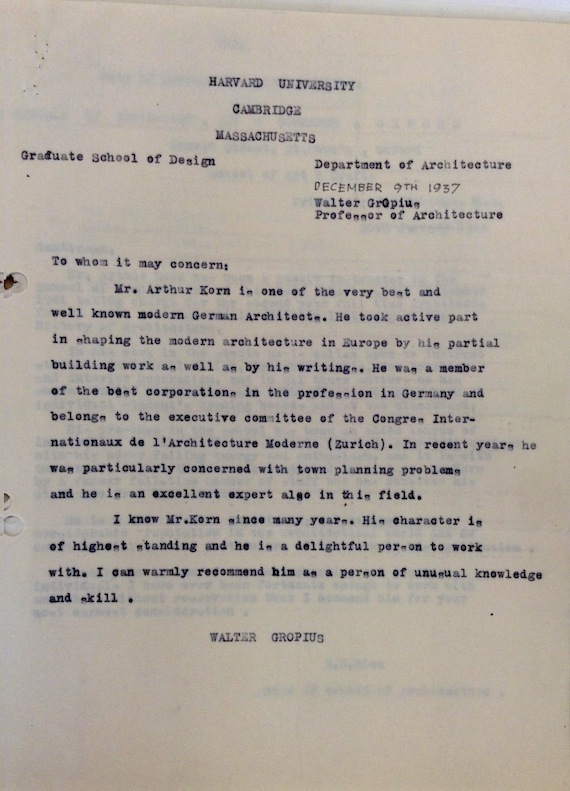

In 1934 Korn returned to England with reference letters from Walter Gropius, Maxwell Fry and others to recommend him. Gropius in particular highlighted that Korn ‘belonged to the executive committee of the Congres Internationaux de l’ Architecture Moderne (Zurich). In recent years he was particularly concerned with town planning problems and he is an excellent expert also in this field’.[13]

In England, Korn worked with F.R. S. Yorke (1938) and with E. Maxwell Fry (1939) and participated at the MARS Group exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries in 1938.

But this is where he started to halt.

Firstly, because he was less famous than Gropius and perhaps less well connected than Mendelsohn in a country that did not warm up to modernism so easily. Secondly, because of his politics.

Many modernist émigrées found themselves professionally stranded in England. Walter Bor remembers the ‘disbelief and mounting disappointment at the seemingly interminable repetition of the same rows of mean little two-storey terrace houses’. [14] Language created an initial barrier (notably for Mendelsohn and the artist Nikolaus Pevsner), and fellow émigrés did not always want to lend a helping hand: ‘Gropius did not like working with foreigners (i.e. those who were not British) in his office, and did not lightly employ or support them’ remembers Walter Bor.[15] In addition, British modernism was severely lagging behind continental housing. This gradually changed from 1933 onwards. Walter Bor remembers a certain arrogance in the Bartlett School of Architecture’s recognition of modernism. [Albert] Richardson[16] the advocat of neo-Georgian tradition, insisted on ‘forgetting all that Bauhaus nonsense’. He adds: ‘Richardson hated le Courbuisier, forbidding the mention of his name’.[17]

The climate for CIAM and MARS architects in England was chilly up to the 1930s, and its legitimacy needed time to establish. When CIAM sent a letter to Howard Robinson, inviting him to attend the meeting in October 1929 and to organise the English branch of architects, he replied with great suspicion:

‘In the first place we have not here a modern movement similar to that in Europe. The average English view to what is modern in the form of housing does not I think correspond with that Abroad. There are, for example, no Housing schemes of the type which I have seen in Germany and elsewhere. (…) As regards an exhibition, it is quite impossible to prepare this at such short notice. In the first place there has recently been an exhibition for which many architects have loaned photographs, and on the second place English architects are not very interested in sending their work Abroad. (…) For the moment your Congress is not sufficiently well known in England to raise much enthusiasm as regards an exhibition and I personally have not the time to attempt the organisation of even a small one’.[18]

Even members of MARS struggled in the context they were placed in, and this continued after the WW2. In his Introduction to the book Planning and Architecture presented to Arthur Korn by the Architectural Association on the occasion of his retirement, Edward Carter remembers: ‘We describe ourselves as modern architects and may wake up to find that we have not got a modern world, but that merely the architecture has decayed, or that it is even the architecture of the past decade that we have been talking about’. [19] At MARS Group meetings, architects are grappling over the use of term ‘modern’ versus ’emergent’ or ‘contemporary’ in attempts to accurately describe their work in relation to the context of the postwar Britain.

In this environment, Korn’s strong socialist leanings did not endear him to his peers. In his obituary tribute to Korn, E. Maxwell Fry says: ‘When I first met Arthur Korn as a member of the MARS group his vehement Marxism made me think him a demagogue. But when I listened more closely to his idealistic themes of planning; when he repeated himself; and when the severely rolling eye relented on recognising me as a pupil; I knew him as a pure-blooded pedagogue, and took him to my heart’. Not only ideologically biased, this obituary also signals that Maxwell Fry has made his mind up that Korn may have been an excellent teacher, but is not cut to be a town planner in the UK: ‘My experience on the RIBA Council told me that subversive politics and architecture make poor bedmates, and Korn was a good architect. Then as I listened, and at times impatiently, to the laborious dialectic inescapable proof of his assertions, I came upon a delicacy of mind and a quite separate critical apparatus that owed more to artistic enthusiasm and a warm heart than to any system of reasoning, and at this point we became friends’.[20]

Korn, who was forbidden to practice architecture in Germany, had to enter professional organisations in Britain to be able to continue his work. He was entered on the register of architects on 19 October 1945, applied as a Licentiate to RIBA in 1948 and was admitted as RIBA Fellow on 20 July 1949. Maxwell Fry’s written statement in support to Korn’s RIBA Fellowship application placed him squarely in the role of an educator: ‘Apart from work done in collaboration with F. R. S. Yorke I am not acquainted with his work but set the highest value on his influence as a teacher’. This he writes in spite of working with Korn on a project for flats at Shoot-up Hill, London in 1939.[21]

Tellingly, when submitting his biography to RIBA for his Licentiate (1948) and Fellowship (1949), Korn made no mention of his trip to the USSR in 1929, the co-founding of the Collective for Socialist Building in Berlin in the same year, or his three year stay in Yugoslavia (1935-37). The ‘Chronology of Events and Designs – 1891 to the Present Day’ for the Festschrift Planning and Architecture (1967) however lists ‘three interior decoration schemes, projects for three textile factories, Zagreb; Town Plan Competition with Antolić: 2nd Prize’, but it would appear that he didn’t find this of any use during his working life in England.

Instead, in 1939, Korn was interned at the Hutchinson Camp for eighteen months under the Aliens Restriction Act of 1914 and the Aliens order of 1920.[22] Edward Carter notes that his political affiliation might have contributed to his longer detention at the camp:

‘When the war started Arthur Korn, along with all but a few privileged refugees, was swept into the concentration camps crudely designed to enable the authorities to sort out the dangerous characters, generally defined as left-wingers. Some were let out after a few weeks, but Arthur Korn had a political past; indeed his whole architectural and planning motivation was based on socialist ideals and he had had long established contacts with the USSR – when he first went to Russia in 1929 he knew, he said, only one phrase in Russian; ‘I love you’. On his return to Germany he founded the Collective for Socialist Building. These things, insofar as they were known to the British Intelligence, were bad marks on the record and he was held for a year and a half. All of his MARS friends organized an appeal for his release, successfully, but it was tediously slow. In connection with this I was involved in a hilarious interview with a detective, who obviously had been briefed that MARS was a seditious organisation; the name CIAM was in a foreign language which was bad enough and it included the sinister word ‘international’, which the detective pronounced as in the title of the communist anthem, and it took some explaining that two of the first names on the list were Chermayeff and Lubetkin – Russians and obviously baddies. It ended happily enough by the detective saying, ‘What, sir, is it all about?’ I explained that all those Korn supporters wanted white houses with flat roofs – and there to prove it was F.R.S. Yorke’s Modern House in England with illustrations of work by all Korn’s friends, in opposition to the others who wanted red houses with pitched roofs – and there was a Studio book to prove that. Modern architecture can seldom have been reduced to such inadequate definition for a better reason’.[23]

Following his release, employment (even with references) had been difficult. As Peter Moro noted, ‘Doctors and dentists were needed… whereas artists and architects were not’.[24] Arthur Korn found himself continuing his (voluntary) work as a part of the MARS Group, but his address changes frequently for the next several years.[25] ‘Arthur Korn – though influential as a teacher – was barely visible as a practitioner’. [26] Other members of MARS and old members of Der Ring were much more visible: Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry built a house on 66 Old Church Street, Chelsea (1935-36) for Ben Levy, whereas Ernö Goldfinger built 1,2 and 3 Willow Road, Hampstead (1938-39), where he lived with his artist wife, Ursula Blackwell, as well as such notable (and controversial) structures of British brutalism as the Trellick Tower, the Balfron Tower, 2 Willow Road, Metro Central Heights, and the Glenkerry House.

Shortly before his internment, Korn was the Chairman of the MARS Town Planning Sub-Committee, where he put to practice his knowledge of town building and his experience from making a planning scheme for Berlin into a comprehensive planning scheme for London. The Committee comprised of Korn, Maxwell Fry, Godfrey Samuel and de Cronin Hastings. Korn was described as having been ‘the main spring of the enterprise’ and as providing an ‘infectious enthusiasm’ that drove the project forward. Korn’s initial chairmanship of the plan was interrupted by his eighteen-month internment, during which period work on the plan fizzled out. On his release, in 1941, work recommenced but the momentum of the group was directed elsewhere. Korn now worked with Felix Samuely, Maxwell Fry (who was the secretary), and Arthur Ling, and together they organised an exhibition of the plan and published a ‘description and analysis’ under the joint authorship of Arthur Korn and Felix Samuely in the Architectural Association journal in 1942.[27] It never came to anything: ‘more theoretical than exemplary, it exposed principles of city growth in terms of rapid transport and interchange, segregated and diversified industry, and the individual’s need for renewed contact with nature, and this without too much concentration on any point’.[28]

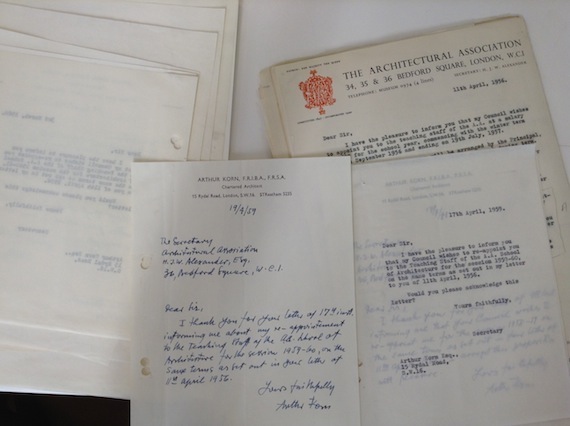

What is apparent from this moment on is that his role in the professional committees diminished after his return from the internment in Hutchinson camp. The MARS meeting minutes reveal frequent change of address, signaling near destitution prior to his employment at the School of Architecture in Oxford, where he taught from 1941-45. Korn’s role in MARS changed from that of a Chairman of the Planning Committee to that of a less prominent member. He no longer published very much. His seminal survey, Glas in Bau und als Gebrauchsgegenstand (1929) was eventually translated into English in 1968 in honour of his retirement, and his second and final book, History Builds the Town was issued by Lund Humphries in London in 1953. His ideas about social housing and planning were instead passed on to his students. From September 1941 till January 1944 Korn was a Studio Instructor in the School of Architecture, Oxford, taking charge of the second year full-time architects and lecturing history. In 1944 teaches in Oxford part-time, since the former member of staff returns to his post from the service.[29] From 1945 commences teaching at the Architectural Association in London.[30] It appears that he is not initially taken on full-time, and there’s a record of his letters about this to the Secretary. He is given a position of a “Staff Planning Critic”, a post he is finally content with:

‘Korn is unhappy in his undefined status. I discussed this and (…) everyone sympathised. The suggestion is that he be offered his appointment as “Staff Planning Critic”, his functions to be planning critic and admin, to give lectures as agreed, to help with relevant studio work, seminars & thesis students. Would he make a particular point of participating in the field planning visits where his experience and outlooks should be especially valuable’.[31]

Korn shines as a pedagogue. His former student, Leslie Ginsburg, says ‘Arthur Korn’s ebulient but sharply perceptive methods of teaching shook us out of the complacent feeling that once we carried out the planning “motions” all would be well (…) always at the end of the day he insisted that it was our duty to aim high, to design only for the best, and to move the economic and political constraints so we could achieve what was needed’.[32] Another student, Stephen Rosenberg, confirms this: ‘A student of his will produce a good design under the impression that he alone has produced it, not realising it was Korn who, without pushing any ideas, has prodded him into it. (…) By his infectious enthusiasm he has managed to bring out much latent talent in outwardly unpromising material’. [33]

Korn’s personal archive could have possibly revealed more of his personal thoughts about this change in his career. Perhaps, like Berthold Lubetkin, he also felt that ‘the parasitic growth has fastened on the early dreams of pioneers (…) The purveyors of frissons a la mode have only succeeded in debasing and eroding those original aspirations, substituting the flicker of change for progress’.[34] This we do not know. Arthur Korn has long been overdue a full-length critical study of his life and work and the circumstances that surrounded him, and hopefully in the future this will be corrected. What we do know is that Korn’s teaching was fruitful and much admired; his planning ideas were in need of expanding in practice. Perhaps he was content in his role as a pedagogue, where he ‘made students see with new eyes’ (Ginsburg). Or perhaps he could have, given chance, pioneered some welcome changes to the urban planning in post-war England.

[1] Biographical details taken from ‘Chronology of Events and Designs – 1891 to the Present Day’, Planning and Architecture: Essays presented to Arthur Korn by the Architectural Association, ed. Denis Sharp, Barrie & Rockliff, London 1967, p. 168-169.

[2] Although brief, Korn’s recollection of the association was full of gratitude: ‘I owe all my further development to Mendelsohn’. (Arthur Korn, ’55 years in the modern movement’, Arena, The Architectural Association Journal, April 1966, 263-5.) His connection with Mendelsohn continued through the work of the group Der Ring. See Appendix on Mendelsohn.

[3] Weitzmann’s documented activity is from 1922-1929. In 1925 he built the Schuhfabrik Hermann Guiard & Co. in Burg near Magdeburg, Germany. Korn’s letterhead from 1928 reads: ‘Architekt Arthur Korn, Dipl.-ing. Siegfried Weitzmann, Berlin W15, Uhlandstrasse 175 (Ecke Kurfürstendamm) Bismarck 8029, DEN. RIBA Archive, Ernö Goldfinger file GolEr/280/2-3 1959-1989, Letter date 5 January 1928.

[4] ‘Chronology of Events and Designs – 1891 to the Present Day’, Ibid.

[5] Programs and Manifestoes on 20th-century Architecture, Ulrich Conrads, ed., The MIT Press, 1976.

[6] Programs and Manifestoes on 20th-century Architecture, Ulrich Conrads, ed., The MIT Press, 1976.

[7] Ross Wolfe, The Graveyard of Utopia: Soviet Urbanism and the Fate of the International Avant-Garde, PDF available here (last retrieved 18.05.2015).

[8] Charlotte Perriand, A Life of Creation, The Monacelli Press, New York, 1998. p. 65.

[9] See for example Myra Warhaftig, Deutsche jüdische Architekten vor und nach 1933 – Das Lexikon. 500 Biographien. Reimer, Dietrich, 2005.

[10] Edward Carter, ‘Introduction’, Planning and Architecture: Essays presented to Arthur Korn by the Architectural Association, ed. Denis Sharp, Barrie & Rockliff, London 1967, p.

[11] ‘Chronology of Events and Designs – 1891 to the Present Day’, Planning and Architecture: Essays presented to Arthur Korn by the Architectural Association, ed. Denis Sharp. Barrie & Rockliff, London 1967, p. 168-169.

[12] This is still the subject of study by Sandra Križić-Roban and myself.

[13] Walter Gropius, letter dated 9 December 1937, the Architectural Association Archive, 2013:13, AG No. 2342.

[14] Walter Bor, A different world: émigré architects in Britain, 1928-1958, Ibid., p. 45.

[15] A different world: émigré architects in Britain, 1928-1958, Ibid., p. 51-52.

[16] Albert Richardson (1880-1964), leading British architect, teacher and writer about architecture. He was Professor of Architecture at University College London, a President of the Royal Academy, editor of Architect’s Journal and founder of the Georgian Group.

[17] Walter Bor, Ibid., p. 53.

[18] Howard Robinson, letter dated 20 September 1929 to the Secretary of the International Congress of Modern Architects, the Architectural Association Archive, MARS files.

[19] Edward Carter, Planning and Architecture: Essays presented to Arthur Korn by the Architectural Association, ed. Denis Sharp, Barrie & Rockliff, London 1967, p. 73.

[20] “Arthur Korn”, E. Maxwell Fry. RIBA Journal, Vol 86, No. 3, 1979, p. 100.

[21] E. Maxwell Fry, Statement in support of A. K.’s Fellowship, 20.7.1949. RIBA Archive, Biographical notes for Arthur Korn.

[22] The Hutchinson Camp (nicknamed ‘Hutchinson University’) was an internment camp in Douglas, Isle of Man, for all German and Austrian citizens (and later prisoners of war) during WW2.

[23] Edward Carter, Ibid.

[24] Peter Moro, A different world: émigré architects in Britain, 1928-1958, Charlotte Benton, David Elliott, Elain Harwood, eds. (1995) exhibition catalogue, RIBA, 23 Nov 1995 – 20 Jan 1996, p. 82.

[25] As judged by the address noted at the MARS Group meetings he attended.

[26] A different world: émigré architects in Britain, 1928-1958, Ibid., p. 105.

[27] Arthur Korn, ’55 years in the Modern Movement’, a paper read to the AA in 1966 and subsequently published in Arena, the Architectural Association Journal, April 1966, 263-5.

[28] Maxwell Fry, “Arthur Korn”, RIBA Journal, Vol 86, No. 3, 1979, p. 100.

[29] Arthur Korn, letter from the 23 September 1944., Ibid. Also letter from E. M. Rice, Head of School of Architecture, to the City of Oxford Education Committee, 20 January 1944. The AA Archive, Ibid.

[30] Letter from 25 July 1945 invites Korn to the teaching post interview at the AA. This appears to come nearly a year after Korn’s letter enquiring after a post.

[31] Letter from W. Allen, undated, to the AA School. The AA Archive, Ibid.

[32] Leslie Ginsburg, “Arthur Korn”, Building Design No. 434, 1979, Feb 23, p. 34.

[33] “The Ring and Arthur Korn”, Stephen Rosenberg, AA Journal, February 1958, p. 170-171.

[34] Berthold Lubetkin, A Letter to John Ellis, President of the Cambridge University Architectural Society, 14.6.1967. RIBA Archive, LuB/13/2/25.

Great blog on Arthur Korn Alexandra. I interviewed one of his students: http://www.monitorproductioninsound.eu/encounter/2016/3/10/qwdi4m57sf7gbfci2yw9q7v0sqltg6 … would be interesting to talk more. I tracked down Korn’s flats in Camberwell, London. Not in a very good state! Are you planning to write more on Korn, or is this as far as you are likely to go? Did he have connections in Eastbourne do you know? John

Dear John, thank you for your comment! Fascinating research over at the Monitor Production in Sound, too! Thank you for introducing me to the Encounter series. Regarding Korn, it was planned for the research to continue but unfortunately the project run out of funds. I am currently planning a translation of some of the findings for publication; there’s undoubtedly more research to be done. I’m abroad at the moment but it would be good to talk more, I’m interested to hear your findings about his students. I’m not aware of any connections with Eastbourne (or rather, I can’t recall reading anything about Eastbourne; doesn’t mean there weren’t any).

The one programme in the Encounter series was with Harley Sherlock http://www.monitorproductioninsound.eu/encounter/2016/3/10/qwdi4m57sf7gbfci2yw9q7v0sqltg6 who trained under Korn at the AA in 1947. At the time of the interview I barely knew of the significance of Korn so didn’t pursue further questions about him with Harley – a missed opportunity! I have Korn’s ‘History Builds The Town’ a curious mix of how towns have evolved and Korn’s own ideas. It is actually inscribed by Korn himself! Interestingly it is dedicated to a person with the same family name as the person I bought it from from Eastbourne – hence my interest in that connection. Might they be a relative? I’ll pursue that one!

The Fromm-Factory was located in Berlin-Friedrichshagen, not in Friedrichshafen.

Many thanks for the correction, Torsten.

Dear Alexandra, thank you for this blog on Korn. I have some addition question to ask concerning Korn, would it be possible to contact me via email, and we can discuss? Look forward to hearing back. Thank you.

Bennett.

Really useful and interesting blog, Alexandra; many thanks and sorry I’ve only just stumbled across it. I am writing a book about Walter Segal currently (I wrote the first one 30 years ago when many of these guys were still alive but not Korn!) Walter and Korn shared an office when both were new to England (1936-7ish)… In your work on Korn have you stumbled on anything about Segal (who revealed the minimum about 1936-1946)? I’d love to hear or talk with you (johnmckean.eu). I had not realised AK was secretary of the Novembergruppe which WS’ father Arthur had also been – but WS never mentions AK in talking of 1920s Berlin – only that AK had been in Moscow same time as WS’ only guru, Bruno Taut, both leaving as Molotov killed Modernism… Thanks again for this good and thoughtful piece.

(PS pity your other posts under ‘drawings’ on this site seem no longer to exist…)

Hello Alexandra — I am working on a project about one of Korns students, Henning Larsen, and I have questions you may be able to reply. If you can find the time, will you send me a mail?

Kind regards, Merete

Hi alexandra, thanks for you great blog on Korn and his invovlement at the AA. Howard Robertson’s letter to CIAM was particularly inlluminating on teh state of English modrn architecture at the end of the 1920s.

Have you published this as a paper yet? If you have not can you tell me when this blog was posted so I can reference it?

Kind regards – Paul Dielemans