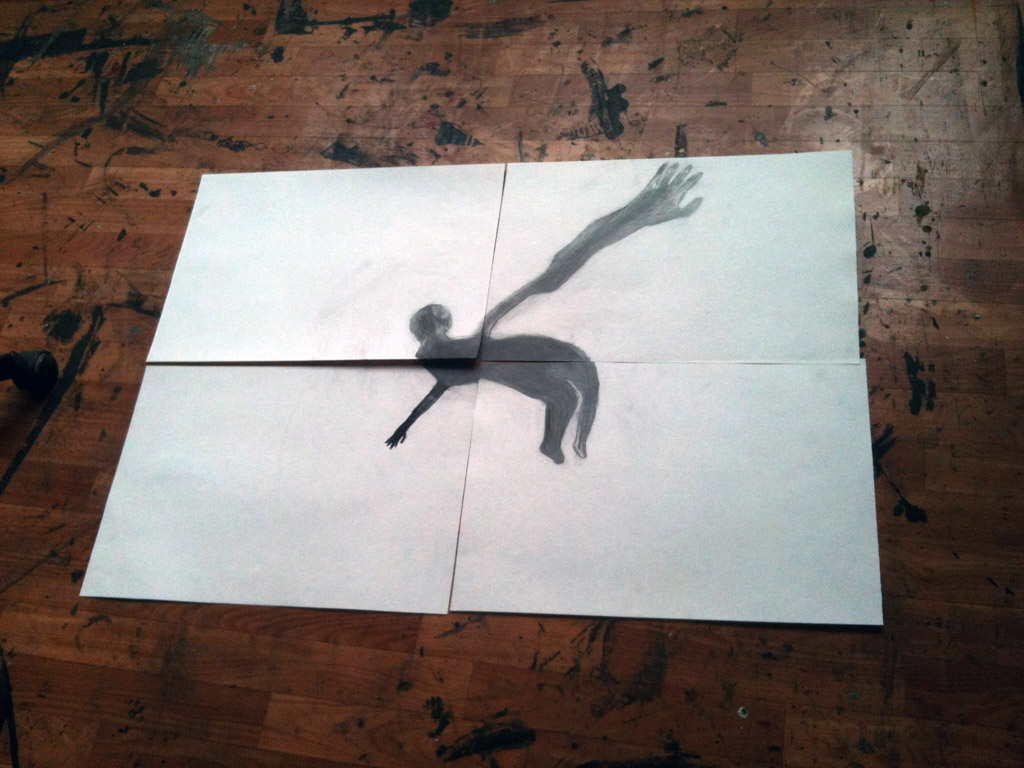

November lollipop (2012), graphite and oil on paper

I rarely want to grab hold of a drawing and run away with it, but that is what has happened when I first encountered the works of artist Dragana B Stevanovic. It was at the Remont Gallery Art Bazaar in October 2012. It was the last day of my extended stay in Belgrade. My friends at Remont have organised a bazaar where, in just four hours, they offered sixteen artists a chance to display and sell their work. I came to say hello and goodbye. It was freezing. I had no cash with me.

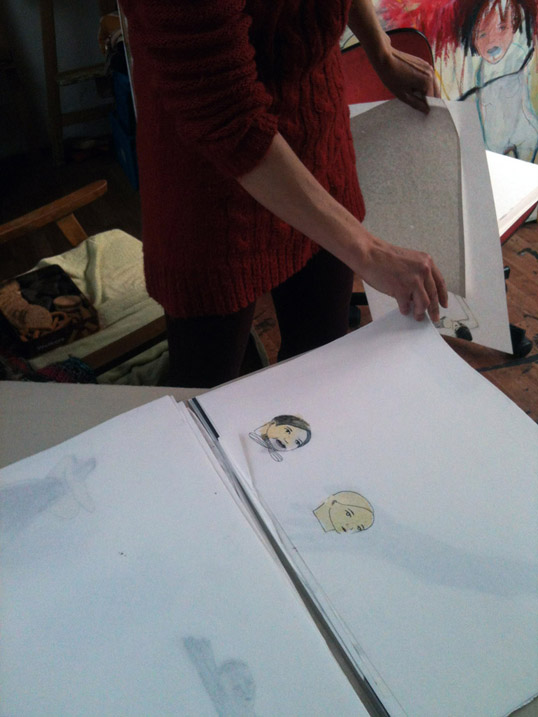

I immediately spotted Dragana’s work piled across a table: prints and drawings of incredible, mucky delicacy. Luminous shadows – as someone called the works of De Sade – creamy, articulate and charming. For the first time in ages, I wanted to acquire one. Most of them. Then I decided to show them to others. To everyone. That’s how Art&Gin was born.

Four months later, I visit Dragana in her studio in Belgrade. A beautiful, intimate space opens up behind metal door of a small shopping mall complex. To reach it, I walked across a market that sells autumnal vegetables and flowers, cramped shops that offer plastic goods or repair clothes. Dragana offers me some fruit tea and biscuits. The room is radiant with her paintings. We start chatting.

For those that haven’t yet seen them from up close, Dragana B Stevanovic creates visual language from a highly reduced human figure, using it as a cypher or a graph (which is the surface form of a grapheme, the smallest semantically distinguishing unit of language) positioned on a flat plane. Her drawings are conceived as reduction, simmering down to the point that doesn’t quite equate abstraction but can no longer be considered figurative.

We begin the tour of her studio in a way that resembles her approach to drawing: by exclusion. She tells me what her work is not: the figures are not interpretations or metaphors of moods or emotions; they do not serve a narrative or aesthetic purpose. Although viewer is welcome to unravel their own meaning, for Dragana drawings are simply spatial forms of variable density that explore the edges, limits and balances of surface.

From Inner pleasures (2009), and Different natures series (2009).

The drawings are conceived as open forms, loosely anthropomorphic but frequently having additional attributes (such as animal parts, multiple heads or swappable genders), in some correlation to sequence, but almost always solitary. Even when given a ghost shadow or a double, the figures maintain a sense of isolated presence and concentrated weight that pulls in on itself, locks in. These are private forms. They stoop; cry; help themselves with wing-arms on their head to shift back on the rectangles of paper from which they’re about to fall off; they ponder. They ponder a lot. They are often reminiscent of something so archaic that I have no word for it, other than ‘ow’. They are monosyllabic, or entirely soundless.

Yet, Dragana’s drawings contain more. Space around the figures inevitably contains some form of white noise, or hidden ligatures, that reveals the figures’ inherent ambidexterity. We talk about this, and Dragana reflects on her fascination when she was shown her first ambigram: a portrait of a smiling face which, when the paper was turned upside down, suddenly appeared sad.

We have all seen or tried to draw optical illusions such as these. Human interest in perceptual reversals dates back to antiquity, and images that contain perceptual multistability famously feature in the work of M. C. Escher and the whimsical portraits of Rex Whistler. However Dragana is not making a joke: by using a difference between the left- and right-brain perception, her drawings challenge immediate assumptions about how things should look or what they should do. Today she draws and paints by turning the paper or canvas throughout the process, juggling the planes of surface and meaning in a desire to capture not just an inter-textuality but also the inter-legibility of form. Her figures are not graphic or optical riddles, but they have their hidden aspects. Cords and tensions that connect the figures are near invisible, executed in a filigree work of erasure lines and translucent nuances of white on white background. The drawings are conceived like spontaneous anagrams, ambigrams or designatures – meant to be read from various angles until they balance themselves in the right light.

As a pupil of the late sculptor and theoretician Kosta Bogdanovic (1930-2012), Dragana carries the guiding principles of his work in her treatment of form (reduction from cluttered to essential), close attention to material, purity of colour, and a close connection with body. Bogdanovic, who taught visual theory at the University of Novi Sad where Dragana graduated in 2001, was known for his pioneering theoretical work in the field of visual culture as much as for his minimal sculptures. His treatment of human form, influenced by his understanding of sign and symbol, demanded clarity and reduction. Dragana’s drawings are similarly dense, pebble-like and monolithic. Although she does not consciously reflect on Bogdanovic’s symbolism, there’s a visible affinity and awareness of sculptural space, gravity and weight. [1]

However, where Bogdanovic’s use of colour was esoteric in its purity (alongside natural hues of wood his sculptures were block painted in ultramarine, gold or white, the colours of Byzantine mosaics and frescoes, reflecting spirituality distilled from the natural world), Dragana uses colour to add or subtract depth to her figures. Her colour remains subtle and faintly polychromatic, relying on the density of line and form against the white space.

Rhythmically, she plays with templates (body doubles?) that she places across several sheets of paper suggesting mobility, displacement, multi-focus, residue, shadow and mortality. Working across multiple frames, Dragana observes how various elements correspond in different groupings, alluding to the notion of an open space and belonging to a bigger thematic concept, of which any isolated drawing is only one part. This in-betweenness of movement and space reminds me of three dimensional paintings by Susan Weil, and it is also present in her oil painting Curtis puppy (2011-12), where the plane of the painting is irregularly divided in two segments, resembling a film strip stopped mid-flow. Whereas the motion in the painting appears to be stopped, the segmented drawings accumulate motion and arrest attention in the gaps, like water between tiles. It would be interesting to see how Dragana will continue exploring sequencing and polyptichs in her further work, and whether it will bring her to experiment with other media; however what I found interesting was this near-anamorphic exploration of two-dimensional plane and perspective that, without any use of extra-sensory tricks, forces the mind to make mental and physiological shifts guided by drawing.

Dragana’s interest in body is shown in her treatment of the figures-as-graphemes (which are given cuts, openings, genitals, beards, breasts and body parts that can be reordered and reorganised like in an anagram. Her lithographs and etchings take this further, by duplicating the lines exactly onto itself in a contrasting colour, or by doubling up the line), but where the body reveals itself at its most lavishly resilient is in her treatment of paper. Dragana chooses her paper carefully, as its weight, texture, opacity and nuance are important building blocks whose pristine, tactile skin and taut surface is as informative as that of the ‘wound’ of a drawing. She prefers warmer white paper, which she overlays with thin layers of colder or brighter white paint, or interchanges with more translucent crystalline white of the parchment.

Dragana works in scale that reflects her physical stature. Her formats are never bigger than what she can grasp and carry. She commented on the practical aspects of this, but the aspects of motherhood and birth were underlying too.

Dragana’s physical approach reminded me of Barbara Hepworth’s small-scale sculptures from the early 1930s, especially Mother and Child (1934), where a separate maternal form enwraps a smaller one. Hepworth talked about this in her analysis of her interest in the counterpoint between the interior and exterior of sculpture and of conception of the forms in terms of the maternal body: “I have always been fascinated by the relationship of inner and outer form. The relationship of a nut in a shell – or of a child in the womb – or the amazingly different qualities of, say, the inner and outer surfaces of shells or of crystals”. [2] It is possible to talk about ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ in Dragana’s work too, in relation to buildup of line and texture, light and space, and puncturing density of shape and line – also quite Hepworthian. Another sculptural quality of Dragana’s figures is the feel of waxed, polished shapes in luxurious strokes of wax, oil stick and gold. But where Hepworth remains aware of her horizon (in her interest in Greek myths, pagan landscapes and esoteric symbolism she connected the horizontal plane to the Earth mother principle), Dragana gives each of her works at least four horizons: each form is invited to have multiple origins and multiple symmetries.

Recently, some of her forms are beginning to sprout several heads, or several bodies connected with the same head. They have some of the raw power of the multiply-limbed prehistoric cave drawings, carried with contemporary aplomb. They do not suggest split-action movement, but inner divisions and crossroads. A head with a body of a hairy bodybuilder sprouts a (fantasy?) body of a reclining woman. Its bodybuilder half cradles his (her? Hir?) genitals protectively. A female form appears to be walking unaware of a hovering cloud of a larger, sensibly dressed and heeled female, sprouting from the back of her head. Another two forms share their head space: does it bear any reference to the duality of human mind? Or the altered paradigm of relationship between gender and the corpus callosum, the one that rethinks the 20th century notion of the ‘male’ vs ‘female’ brain? Or are these just outer reflections of growth and decline? We’ll have to wait to find out.

Inner Tour series (2013)

Photography and text by Alexandra Lazar © 2013, except for November Lollipop, Inner Pleasures, Different Natures and Inner Tour, photographs by Dragana B Stevanović.

_______________

Notes

[1] Kosta Bogdanovic’s book, Visage and Face, published in 2011, is a concluding tome of his trilogy on visual theory.

[2] ‘The Sculptor Speaks’, British Council recorded lecture with filmstrip, 1970, TGA TAV525