The first task of critical history is not erasure of its own past, but critical forgetting of its fake glory.[1]

– Todor Kuljić

In an interview with Dragan Papić for Reporter in 1981, art historian and curator of SKC’s Happy Gallery Dragica Vukadinović called him ‘the chronicler of simulated situations’. The title referred to his 1978 series of erotic polaroids ‘Meso’ (Meat) and ‘Plastika’ (Plastic), but it could have just as well applied to his prolific documenting (and fabricating) of the Belgrade new wave art scene, including his involvement with the band Idoli. Influenced by McLuhan and interested in media manipulation and socio-politics, Papić was a seasoned art insider who explored and exploited the interconnections of the 80s fascination with image-making. Prolific, observant and socially well-placed, his interest in layered networks, histories and meanings took a different shape in the Inner Museum.

Inner Museum (or UM for short[2]) started from the small collection of replica statuettes that Papić collected from the vicinity of archaeological excavations since 1976 and continued in parallel with his other artistic projects, growing from an installation of alienated memories of post-socialist past to a fully-fledged one-man museum. Since the mid-nineties the collection was shaped as an ambient, layering of objects precipitating the process of finding and detecting memory. Although the artist claims that the concept for current physical form of UM as Gesamtkunstwerk (i.e. a total, comprehensive art and not an expanded installation) came as early as 1995 in a conversation with Rasa Todosijević, a large part of his process is time. It is important for him as an artist that this collection represents process or a journey, where individual objects are simultaneously fetishised and ignored, relevant only as windows of insight in each participant. UM thus served as a laboratory and communication device at the intersection of personal and collective memory, investigated via the overlapping approaches of performance art, psycho-linguistics, sociology of history, neuro-psychology and urbanism. On René Block’s suggestion, UM was included in 2006 October Salon exhibition, thus reaching the peak of its active communication with the audience. Closed for public since 2007, UM remains an aesthetic and theoretical space for potential future dialogue with artists and theorists.

Objects in a traditional cabinet of curiosities are, in a way, cultural outcasts from another era, momentarily redeemed by their inclusion in an alternative version of a carefully crafted and constructed past that, having lost some of its scientific or religious aura, are now left as peculiar, exotic intermediaries of memory. The Inner Museum collects objects, relics and oddities of post-socialist life in what used to be the capital of Yugoslavia. Both the collection and its creator seem, like the objects, outcasts from another era, but only momentarily. The wild landscape of this collection may appear to be related to similar collections of discarded history shown in flats, galleries and museums across Eastern Europe since 1989, but unlike many of those the Inner Museum is not concerned with remembering, but with forgetting, as Papić engages in the task defined by Todor Kuljić, the ‘critical forgetting of [history’s] fake glory’.

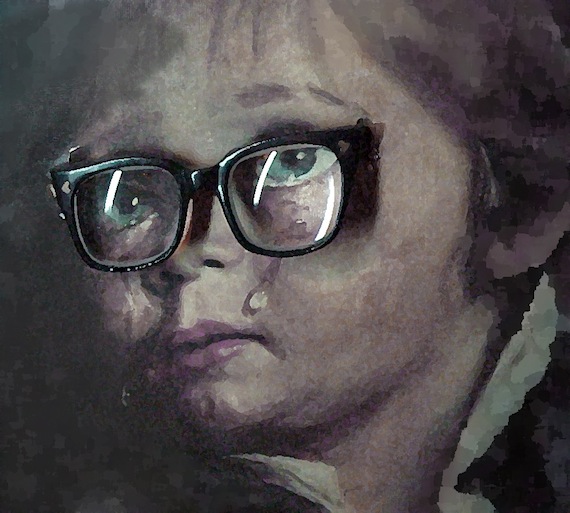

The Inner Museum is a Kunst und Wunderkammer collection of sorts, resembling surrealists’ ambient assemblage and an interpretative and meditative performance space. It’s a work with which the artist liberates himself from concepts of prescriptive history, ideology and progress by housing a collection of objects, each of them standing in for some memory, association, pun, myth, provocation – within a labyrinthine non-hierarchical space, in attempt to recreate a multi-faceted, multi-dimensional collective memory landscape… or a minefield. Papić also places himself within this Museum, as its narrator and in many self-portraits in which he transforms himself into a weeping child, stuffed teddybear, a jolly toy car or a vomiting house front. His role becomes as complex and broken as the museum itself, which serves as his double.

Dragan Papić has been active on the Belgrade art scene since 1978 and is best known for his photography, social and urban activism and various strands of ‘post-conceptual and (as he terms it) nulti-media’ work. Formed through modernism, he sees himself as a representative of the second generation of Belgrade conceptualists and as such remains intent ‘to reconcile Mediala and Belgrade conceptualism’ as pop-conceptualism. Peer of Serbian conceptualists Marina Abramović, Rasa Todosijević and Era Milivojević, Papić has always been an avid chronologist and critic of Belgrade art scene. His first project involved media campaign managing a group of artists and musicians named Dečaci (Boys), who later became known as Idoli – one of the cult bands of the Belgrade new wave of the 80s.

At the outbreak of war in 1991, Papić left Yugoslavia for Italy and although he returned in 1993 this absence and subsequent status as war deserter has greatly affected his life and work. Papić believes that his relatively short absence has prevented his further social integration, creating an ‘invisible lustration’, social exclusion of those ‘who left when it was most difficult’. Papić’s work on Inner Museum has lasted over the past fifteen years, growing organically from early sculptures and smaller installations and his frequent meditative walks through Belgrade flea markets. In his walks past the heaps of discarded household objects, porcelain figurines, toys, weapons and various socialist insignia, he sought the objects that could provoke or inspire his ongoing stream of thought. This archaeology of litter and rejects resulted in a mass of provocative, unrelenting and humorous pieces that constitute the Inner Museum.

Experiencing Dragan Papić’s Inner Museum is like walking into a post-surrealist nightmare debris. The place itself is Papić’s family home which, until recently, artist shared with his daughter. Every surface in the house is covered with his work, and every piece has a multilayered story, reflected in its title, meaning, history, and correlation with other objects. This way, Papić created a visual narrative that aims to reconstruct and comment on the past and provide both its author and his audience with some sense and meaning.

Aspects of the Inner Museum free-form associate the grotesque aesthetics of kitsch, pop culture and music, cartoons, porn, gossip magazines and trashy entertainment (most notably, so-called car crash TV), only to reveal themselves to be about something else. New Grotesque and carnival culture, coming mostly from the West, is often critical of high gloss and prescriptive middle class values of the establishment, of their legitimacy, consumerism, eternal youth, perceived political correctness and technophilia, and offsets it by contemplating its own fascination and flirtation with seedy and disturbing underbelly of baser human nature, changing face and fashion of cruelty, ‘freakishness’ and death. Although Papić’s Inner Museum has not been imagined with the new grotesque in mind, its aesthetic and presentation certainly flirts with some elements of a carnival show. The artist’s own reference was that of the 19th century collection of Cesare Taruffi, housed at the Museum of Anatomy and pathological histology in Bologna that exhibits specimens and wax anatomical models. The museum also holds preserved organs affected with various diseases. Both collections expose human paradox and fallibility in shocking, but very different ways.

According to critic Stevan Vuković, the Inner Museum is a radical example of ‘performing museology’, defined by anthropologist and performance studies scholar Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett as a method where performance serves as organising idea. Papić not only legitimizes cultural material as art objects, he also ‘changes the manner of interpretation of the content from the informative to performative one’ (Vuković). However, accurate interpretation of the Inner Museum hinges on understanding the brittle balance between this ‘performing museology’ and the productive oblivion (Nietzsche).

UM simultaneously functions as a traditional home (an apartment in a 19th century block of flats) a miniature version of Yugoslavia (with its debris, invisible boundaries, symbols, clashing hierarchies of power represented by classical oil paintings defaced by hunting trophies that pierce their surface, etc.), and the body of the artist, his tool for self-recognition and self-presentation, his hiding place, prison and costume. It frames Papić’s performance with various levels of familiarity/unfamiliarity, sense of occasion (the attendance is precisely arranged in advance), contradictions and tensions between the ephemeral and the historic.

The performance is not completely without direction. Authentic communication and knowledge sharing is its key purpose. The conversations between the artist and the audience are spontaneous and unrehearsed, but they have the beginning, the middle and the end. Firstly, the artist/host introduces UM and its contents with a short tour through its rooms. The rooms are dark, illuminated by artificial light like a body irradiated from the inside, and it smells like an old attic. This presentation contributes to the theatricality and authenticity of the experience: we all love old attics and recognise them as spaces for finding the forgotten, as keepers of secrets, but we also rely on the darkened room before a curtain goes up to create a boundary for the performatic experience. The tour is hasty, which necessitates addressing the artist with questions related to specific objects in order to start a conversation about and around them.

The space consists of three rooms open to the public; the visitor moves from the entrance to the sitting room, glances into the living room and is then introduced to the kitchen and sits on one of two professed chairs. Exactly opposite, behind the raised kitchen counter, the artist takes his place in a traditional heart of home – in a belly, or a hearth, traditional locus for trading stories. However, this kitchen is covered with objects that render it almost unusable; it’s a hearth that needs to be initiated back into life. This is where the second part of the performance takes place, and it is what Joseph Roach understands as transfer and continuity of knowledge and memory: ‘Performance genealogies draw on the idea of expressive movements as mnemonic reserves, including patterned movements made and remembered by bodies, residual movements retained implicitly in images or words (or in the silences between them), and imaginary movements dreamed in minds not prior to language but constitutive of it’.[3]

Papić is expressive and invites expression. He never sits down – instead he stands, moves, waves arms, serves, brings and guides the conversation. This part lasts as long as there are words, silences, gestures and memories to exchange. Kinetic memory of UM is therefore shaped by the multidirectional knowledge and memory of the host and his visitors, and the topics can range from trivial references and symbols, memories and personal histories, political, and socio-linguistic debates, comparisons (of events, people, experiences), often meandering in and around the trauma of the 1990s, reconnecting it with real people, bridging generational divides, explicating and re-affirming that the experience was, in some ways, shared, and in others remains individual and separate.

The exchange of Papić’s performance relies on what Derrida terms ‘event of speech’ (with its importance of citationality, interability, performance of dialect and slang, reminding of phrases and codes of the 1980s and 90s), but it also relies on what’s left unspoken. Silences fall and, like grieving, they allow things to settle. The host and visitors catch breath, drink, glance at one another or at the objects (that serve as topical tangents or entry/departure points) display nonverbal understanding, share a ‘body’ of the Inner Museum, remain with the darkness of what’s been spoken. Inner Museum, although swamped with words, is not logocentric; if anything, it uses speech as a purification exercise that leads to catharsis.

The accurate interpretation of the Inner Museum hinges on understanding the balance between its ‘performing museology’ and its critical individual oblivion (Nietzsche). In contrast to an official or ‘legitimate’ archive that purposes to remember ‘history’s fake glory’ and political amnesia of all else, the Inner Museum remains a site for porous, individual, contradictory embodied remembering and forgetting. The dynamic of the Inner Museum at times resembles a 17th century anatomy lesson (with its penchant for dissecting eras, events, memories and memory triggers) and at times reveals itself to be a precisely navigated tour through ideological and political debate where objects stand in as symbolic guides through and manifestations of a complex culture memory, that is gradually revealed and negotiated (yet never truly fixed) with each visitor. The Inner Museum can only take one visitor at the time, two at most, so it allows for intimate, almost confessional negotiation of layers of forgetting (and what we allow ourselves to not-forget) that remains between Papić, his guest, and the surrounding objects.

Like performance theorist Peggy Phelan, Papić believes that art lives for as long as artist is there to defend it, and that it loses its essence when artist dies or is no longer present to painstakingly explain his vision.[4] For as long as art remains in this ‘inner’ museum, in his intimate, personal space, he intends to fight against it becoming a cultural commodity. However the nature of his performative transmission suggests that he is aware of leaving residue memory through the Inner Museum – something that will remain with the viewer after the artist is no longer present.[5] In his direct engagement with audience and enabled (enhanced) by his junkyard instrumentarium, he guides through various imagery and concepts, activates and triggers meanings, thus reversing the irretrievable process of artefacts becoming dead ‘content’ in a traditional museum or gallery space.

His performance, i.e. his ‘defense of art’, is tailored towards a small audience: Papić engages with them in a conversation that can be as probing, political, angry, informative, personal, fragmentary as they’re prepared to endure. The intense ‘show’ and interaction with the artist can last anything from two to five hours, spiralling deeper and deeper into a complex debate, never once becoming repetitive or becoming too tangential from art. Theoretically, this could go on indefinitely: the visitor remains present until UM settles inside them (in the form of Stomaklija, shared breathing and narrative space), but it is also the visitor that thus inhabits the body of the artist.

What you become engaged with, along with the artist, is healing of collective body. The defence of art becomes a real, reciprocal process of freeing of objects and memory, overcoming the past by establishing a common field ranging from the relative and unofficial histories, politics, architecture, culture, art and language to the metaphorical nuances of anecdotal experiences. The third and final part of UM is its residue of memory, the precipitate revival, and a constellation of emotions on the scale of grief, sorrow, fear, limpness, curiosity, liberation, joy, recognition and forgiveness.

Significant portion of the Museum is the Wall of Memories. This seemingly haphazard collection of souvenir and decorative plates depicts various locations to which their anonymous owners have travelled while their visas still allowed them to. They also commemorate workers’ unions that no longer exist, ideologies that have since been abandoned, celebrate holiday locations that used to be ‘in our country’ and now no longer are. The plates were often a link between different generations of owners, who each added a plate from their life on a wall in their house. These were often poor households and the plates were not many; Papić collects them at flea markets once they’ve become discarded and devalued, presumably replaced with newer, better memories.

In addressing the question of inventing past in the Balkans in his book Memory Culture, Serbian sociologist Todor Kuljić offers a potential framework by which to interpret the Inner Museum. Kuljić talks about deterministic invention of past which he calls ‘retrospective fatalism’. Retrospective fatalism in official recent Serbian history is closer to mythical memory than to critical historiography. It suggests that Yugoslavia had to fall apart as there was no other alternative. This invention of past is determined from a glorified and monumental view of nation, in which the histories of Yugoslav nations are separated from that of the multinational federation. In the view of normalised nationalism of the 90s, the fall of Yugoslavia was not only predetermined, but its socialist period will historically remain tabula rasa, an inorganic part of history that brought nothing positive or good. Siding with this new ethnocentric ideology, the public was prepared to see their socialist past as totalitarian, oppressive, artificial and perishable, as to claim the opposite would be to challenge the new ideology and would result in being labelled as ‘yugo-nostalgic’. This is why there are so many souvenir plates that are no longer desired; they represent emotional treason to the ‘new’ nationalist consciousness. Ex post facto and imperatives of the new memory order created a dogma that is, essentially, as totalitarian in its anticommunist view of the past as was the old communist orthodoxy. Papić responds by showing inconsistencies in this retro-fatalism and highlighting similarities between past and present dogmas by showing them side by side, embodied as collectable souvenirs.

The power of memory stems from a possibility to successfully impose on an individual a feeling of belonging to a community of memories which strive to set out its own interests as common ones. This ‘mobilizing role of the past’ is often used within ideologies that present a selected, specific instance as universal in order to give them social significance, consolidate authorities, and legitimise power. Inner Museum plays with this selective use of public memory and oblivion which inevitably ends with imagery that many find provocative: he mixes socialist paraphernalia with children’s toys and souvenirs, gives dubious ‘cool’ to a war criminal Ratko Mladić by superimposing his image on a Guns’n’Roses printed shirt, uses worker union pins to create map of Yugoslavia, creating a map of disappearances by associating the dismembering of unions with dismembering of the body of state.

One of the crucial aspects of UM remains its specific, live communicativeness: the use of form that structures memory. Moreover, it relied upon intellectual and emotional investment – in other words, a friendship – to question and re-create sense, while the archival architecture of UM acts as a bridge across the potential abyss of memory and trauma.

In parallel with UM, Papić became increasingly active in producing PLJUS – Prostor Ljubavi i Slobode – a mailing list with which he experimented with publishing, research, organisation and web broadcasting to a range of recipients. PLJUS worked towards creating a different kind of dialogical archive, using digital technology in the field of political composition and meshing socio-political themes with urbanism, modernist poetics, pop-cultural references and the conceptual post-structuralism. In some ways this was a continuation of ideas of UM (where one-on-one dialogue was paramount), and in some ways it was its opposite: disembodied, fragmented, libidinal cross-posts where the artist’s editorial voice provided consistency of references but also effected control. The digital communication and archiving provided Papić with an abundance of multi-stranded topics and intensification of productivity, but also caused hypermobilisation of his nervous energies and frequent information overload (what Deleuze and Guattari called the psychotic-panic framework of the first connective generation). After the initial active phase, the list has undergone tapering down of communication, reducing the number of its recipients. The artist writes openly about experiencing depression, disconnectedness and anxiety in this later period, which alludes to the ‘physical and psychical solitude of the infospheric individual’[6] and is symptomatic of the information overload and disinvestment of energy. This depressive shining was absent from UM, where physical presence and materiality of experience and time played an important role.

Papić’s Inner Museum is a good example of performative archive that locates itself outside of the official flows of memory, including the memory of the black market. The cultural production in the decade of the millennial transfer of the last of Yugoslavias has often reflected some aspects of junkyard nostalgia and assemblages. Reflections of UM can be gleamed in the work of Vladimir Perić and Miloš Tomić, although only superficially so. Whereas the pair construct environments with some forms of ‘garbage’, Peric’s Museum of Childhood at the 2013 Venice Biennale showed a highly designed, tasteful kookiness, whereas Tomic’s juxtapositions lacked deeper understanding of history and social strata. Unlike the optimistic hyperproductivity of underground-savant Saša Marković Mikrob or the touring collection of sentimentality in the Museum of the Broken Relationships, UM does not circulate, display or disperse itself. The former are essentially pleasant, optimistic or nostalgic collections of clean, neutered politics that harness the faint memory of black market and alternative production, which inherently refuses to be evaluated, creating foci for distribution of neoliberal concept- and exchange-value principle. The key difference between these works and UM is their palatability and desire to extract from decay, rather than to testify its forgetting. UM is an archive of ‘unimportant’ objects and important cognitive connections that, in its perfomative years, served as a platform for critique and reconnections, and in its closed state stands as for planned entropy and forgetting.

[1] Todor Kuljić, Kultura Sećanja. Teorijska objašnjenja upotrebe prošlosti (Culture Memory. Theoretical interpretations of use of past), Čigoja press, Belgrade, 2006, p. 290.

[2] ‘UM’ is shorter for ‘Unutrašnji Muzej’ but it also means ‘mind’.

[3] Joseph Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance, New York, Columbia UP, 1996, p. 26.

[4] ‘Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representation… Performance’s being, like the ontology of subjectivity proposed here, becomes itself through disappearance.’ Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: the Politics of Performance, London, Routledge, 1993, p.146.

‘performance does remain, does leave residue. Indeed, the place of residue is arguably flesh in a network of body-to-body transmission of enactment’ (102) ‘Archives: Performance Remains’, Performance Research, 6, 2 (Summer 2001), 100–8.

[6] Franco Berardi, ‘Inversion of the future’, After the future, ed. by Gary Genosko and Nicholas Thoburn, AK Press, Edinburgh and Oakland, 2011, p. 62.